|

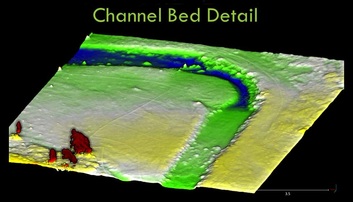

By Emily Davis  University of Oregon graduate student deploying heli-kite with digital camera attached University of Oregon graduate student deploying heli-kite with digital camera attached Aug 24, 2015 Researchers use low-cost techniques to produce high-resolution images of new river channel construction in the Oxbow Conservation Area The Oxbow Conservation Area (OCA) on the Middle Fork John Day River (Middle Fork) has been the site of some ambitious and impressive river channel restoration projects in the last few years. The big question on everyone’s mind is: How can we monitor our restoration projects to see what kind of change takes place over time, and hopefully connect that to changes we see in fish populations? And how can we do it effectively, without expending too much money or time? Researchers at the University of Oregon think they may have the answer to this riddle. Using a creative approach and a unique assortment of tools, scientists from the McDowell Geomorphology Lab are using a technique that, in just an afternoon, can collect more data than an army of students could collect in a whole summer. Decades of gold dredging and other channel straightening activities made this reach of the Middle Fork an unfriendly place for fish. The channel reconstruction project on the OCA took a straight, relatively uniform stretch of river and turned it into a more natural meandering channel with more deep pools. The hope of the channel reconstruction project was to provide the nooks, crannies, and diversity of habitat types that fish—especially juvenile salmon— need to rest, feed, and hide from predators. So how has the river channel changed since the project was implemented? To find out, UO graduate students working in the McDowell Lab attached an ordinary digital camera to a heli-kite flown over a portion of the reconstructed channel during the course of an afternoon. A heli-kite is a deceptively simple device: just a small helium balloon with two ropes attached and a place to attach the digital camera. It can be easily operated by two people. With one person standing on either side of the river channel, each holding a rope attached to the heli-kite, and the helium balloon holding the camera overhead in the middle, the crew then walks down the stretch of river they are interested in analyzing. As the camera passes overhead of the channel, it snaps a multitude of overlapping images, about one every second. The images are later analyzed using special computer software that matches up the overlapping photos, creating a digital image of the structure of the riverbed. In essence, the software creates a 3-D ‘tour’ of the channel shape using the photos. “It’s analogous to what you might see if you went to a realtor’s website and got a 3-D tour of the inside of a house for sale,” says project leader Dr. Pat McDowell. “Just way more precise, of course.” What can an interested researcher do with this 3-D tour of the riverbed? For one, it allows restoration practitioners to more easily track how their projects are changing the physical landscape over time. Such monitoring has historically relied on very time-intensive field methods, requiring lots of personnel and money to complete. Initial results from 2014 (photo 3) show increased channel bed complexityextensive restoration project. More channel bed complexity could mean improved aquatic habitat for fish and other critters in the Middle Fork. The heli-kite method is unique and simple—and it means monitoring the success trajectory of restoration at the Oxbow Conservation Area and elsewhere on the Middle Fork could get a whole lot easier in the future.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

IMW News Updates

Archives

September 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed